Key Highlights

- Although the total number of enquiries grew by 7 percent in 2019 to reach 2,820,946, trend analysis from 2016 shows a deceleration in growth, from 34 percent y-o-y growth in 2017, to 18 percent y-o-y growth in 2018, and now 7 percent in 2019.

- The Savings and Loans sector continues to lead in terms of platform usage, whilst the Microfinance sector still trails with a paltry 4.71% 2019.

- About 4 out of every 10 enquiries made (39 percent) produced no credit data on borrowers (“No Hits”), reinforcing the concerns that a lot of users have regarding value for money.

- Attributing non-compliance to high labor turnover not only belies a weak institutional governance structure but makes nonsense of the mandatory clause in Section 24 of the Credit Reporting Act 2007 (Act 726).

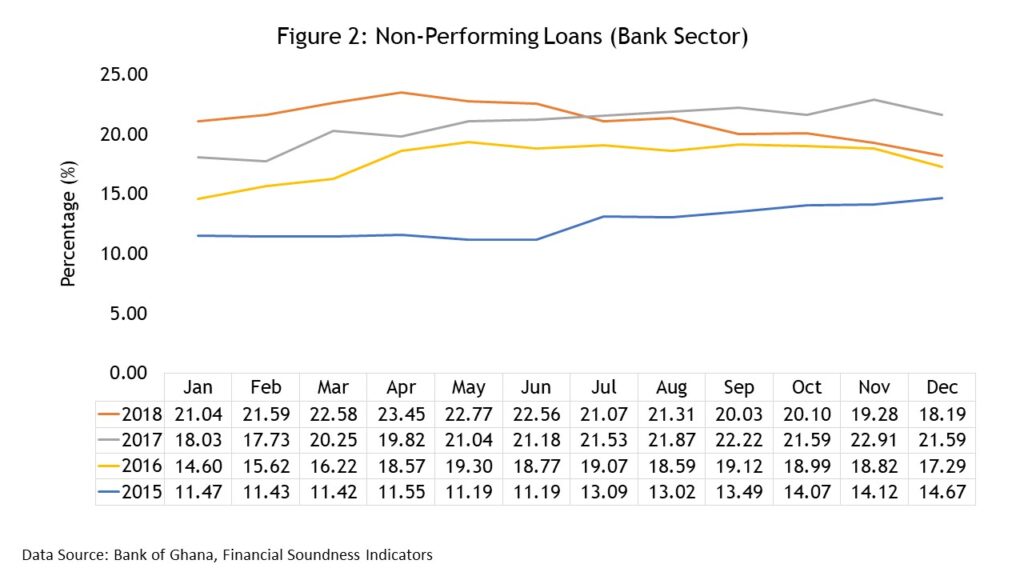

There is no question that a credible credit reference infrastructure yields tremendous benefits to the economy by reducing moral hazard risk associated with lending. Any system or platform that helps to re-balance information asymmetry between borrowers and lenders means that financial institutions are better able to estimate counterparty default probabilities associated with a broad range of assets across several maturities, and can also price such risks more intelligently. Since its introduction in 2008, Ghana’s credit reference infrastructure has sought to deliver this outcome for users. Suffice to say that remarkable progress has been made over the years in terms of adoption and usage. That notwithstanding, there are still major concerns about overall compliance, data quality, and consistent data submission, particularly in the Microfinance sector where it is needed the most.

First thing any keen observer will note is that different provider types within the financial sector are predisposed to using one particular credit bureau, or the other. In terms of share of enquiries, XDSData Ghana Limited is most popular with the banks (51 per cent), followed by Dun & Bradstreet (49 per cent). The Savings and Loans sector also uses XDS mostly (51.4 per cent), but to a lesser degree compared to others. What drives these preferences is really not the focus. What is of utmost importance here is what the broad implications are for compliance, adoption and usage rate.

Here is how it works

First, you need to understand how the system works. Per Section 26 of the Credit Reporting Act 2007 (Act 726), a data provider must conduct credit checks on a prospective borrower before concluding any credit agreement. In order to do that, a data provider, or financial institution in this case, must have a contractual relationship with a credit bureau to use their platform. Almost invariably, every financial institution is signed up with one of the three credit bureaus, for the purpose of utilising their database. On the other hand, Section 24 of the same Act (Act 726) mandates every data provider to submit credit data on a borrower within 72 hours of concluding the credit transaction. The requirement is to submit to all three credit bureaus, using their respective data upload portals. So essentially, reports generated through system query rely on the data submitted by a data provider. Garbage in, garbage out. Quality in, quality out. No data in, no data out. You get what you sow. It’s that simple. This is where the risk is located, and it is indeed an operational risk element. Except where controls exist to ensure that the data clerk actually submits to all three bureaus, the temptation exists to submit to only your service provider, and then maybe to the others, absent any hindrance like system downtime or just sheer negligence. The result would be a situation where, say, XDS Limited may have the credit data for Asomasi Company Limited, but the same data may be missing from D&B’s database, because an employee failed to do his or her work diligently. This is common. In fact, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence to support the claim that this is indeed the practice. This results in what I call the “Silo Effect”.

With about 39 per cent of total enquiries drawing a blank, the value for money question is a fair and legitimate one for the Bank of Ghana to address. What this means is that a data provider receives no benefit for 4 out of every 10 enquiries (approximated) made on a credit bureau’s database, even though facility user fees (cost) have been paid. This runs counter to the cost-benefit argument that justifies the use of the system in the first place. Unfortunately, some non-compliant MFIs cite this reason to justify why they don’t use credit reference agencies. There is evidence (anecdotal) which suggests that some RFIs prefer to share client data via peer-based industry WhatsApp groups for the purpose of obtaining informal feedback on borrower activity. The emergence of such parallel mechanisms has its own problems in terms of data privacy. Clearly, there is a need for urgent action by all stakeholders, particularly the Bank of Ghana, to focus interventions on the MFI sector to increase usage to at least 10 per cent.